Volcanoes already seem like forces that defy the ordinary rules of nature, but some of them go a step further. They don’t just reshape landscapes or spew clouds of ash into the sky — they actually create their own weather. It sounds like something out of a fantasy novel, yet this phenomenon is very real, deeply complex, and still not fully understood. Learning more about how a volcano can hijack the atmosphere helps us appreciate just how interconnected Earth’s systems really are, and how a single eruption can trigger a chain of events far beyond the crater rim.

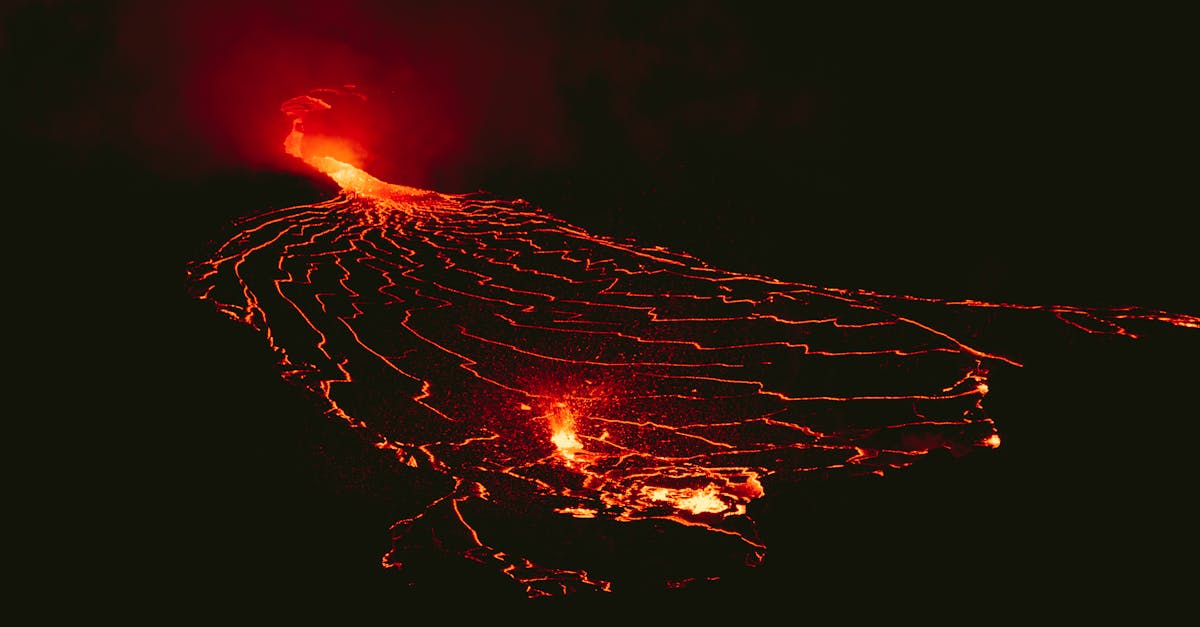

When a volcano erupts explosively, it releases a tremendous amount of heat, ash, dust, and gases upward at incredible speed. This rising column, called a plume, behaves much like a thunderstorm in fast-forward. The hotter and more powerful the eruption, the higher the plume can rise — sometimes reaching into the stratosphere. Inside this churning tower of ash and steam, temperatures swing wildly, creating conditions similar to those found inside storm clouds. Water vapor begins to cool and condense, forming clouds right above the volcano even on what was previously a clear day. People often forget that volcanoes contain enormous amounts of groundwater and melted snow, so eruptions can inject surprising quantities of moisture into the atmosphere.

Perhaps the most dramatic weather a volcano can generate is volcanic lightning. As ash particles smash into each other, they exchange electrical charges, building up static until the air can’t hold it anymore. Bolts of lightning then crackle through the plume, sometimes branching like giant white veins across a dark, ash-filled sky. These displays have been photographed during eruptions from Iceland to Indonesia, and they’ve sparked legends for centuries. Many cultures once believed the lightning meant gods were fighting or punishing the land, not realizing it was the volcano itself forging electricity.

But volcanic weather isn’t just about lightning. Large eruptions can trigger full-scale thunderstorms, complete with rain, hail, and sudden downpours of mud. When rain mixes with ash, it forms heavy sludge that can rush down slopes in dangerous flows known as lahars. Some of the deadliest volcanic disasters in history weren’t caused by lava but by these fast-moving rivers of mud, which behave more like a wet avalanche than water. It’s one of those easily forgotten details: even a volcano that’s not actively erupting can trigger lahars if heavy rain stirs up loose ash.

On an even larger scale, volcanoes can alter regional and global climate. When an eruption injects sulfur dioxide high into the atmosphere, it forms reflective particles that bounce sunlight away from Earth. Major eruptions like Mount Pinatubo in 1991 temporarily cooled the entire planet by nearly half a degree Celsius — enough to affect rainfall patterns and seasons worldwide. This long-lasting climate effect is part of volcanic weather too, even if it unfolds slowly and silently.

One lesser-known aspect of volcanic weather is the creation of pyrocumulonimbus clouds, sometimes called “dirty thunderstorms.” These towering, anvil-shaped clouds form when intense heat lifts air so rapidly that it creates a storm system all its own. They’re better known in massive wildfires, but volcanoes can generate them at an even more powerful scale. These clouds can loft ash into the jet stream, disrupt air travel across continents, and spread fine volcanic dust over thousands of kilometers.

Yet despite their destructive potential, volcano-made weather systems also play a surprising role in replenishing soils and ecosystems. Ashfall can fertilize land, and storms triggered by eruptions help distribute nutrients across wide areas. In places like Indonesia and Japan, fertile volcanic soil is the backbone of agriculture — a reminder that nature’s violence often comes hand in hand with renewal.

To learn about a volcano that creates its own weather is to see Earth as a living, breathing system, where fire, water, air, and rock constantly interact. It’s a dramatic demonstration of how powerful natural forces can blur the boundaries between geology and meteorology. And it shows that even in the most chaotic moments, our planet is following patterns that, while astonishing, have existed for millions of years.